By Couri Johnson

By Couri Johnson

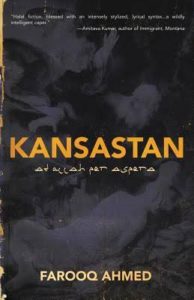

In his new novel Kansastan, Farooq Ahmed mixes dystopia with myth, the Old West with the Old Testament, and creates a narrative that is full of both humor and dread. His un-named narrator, a goatherd abandoned at a mosque in war-torn Kansas, both garners the sympathy of readers while repulsing them. Ahmed positions his narrator against his cousin, a man who can perform miracles, who is praised as a savior that will lead new-Kansas out of war that is ever-raging in the background Ahmed’s novel. But the war that matters most within the text isn’t one of religion or territory, but for affection, as both men fall in love with the same woman, and for the narrator, this is what leads to bloodshed. By setting up this every-day, arguably miniscule issue before a backdrop of an evolving religious landscape and a post-apocalyptic war, Ahmed shows us that even in times of great cultural and spiritual upheaval and the ever-present threat of war and death, it is often our personal obsessions and vendettas that are the most important and interesting.

The narrative’s setting is one of its strongest elements—placed in a future version of United States where the states are no longer united, but separated by religious belief between different factions who are at war with one another. A United States populated with six-legged-cows, mysterious blimps that circle the sky, an ever-raging civil war, Islamic myths, and a new savior performing reality bending miracles. But all of this is just a backdrop for our narrator, left for the reader to wonder over and to draw their own conclusions on. Ahmed doesn’t build this world through lengthy exposition but rather lets the reader intuit and absorb what they will as the narrative progresses, adding in fine, rich details here and there naturally throughout the text and the speech patterns of the characters, creating its depth and texture through rich language that navigates a tender line between the mythic and the humorous.

All these elements are par for the course and take a back seat to our narrator, and so Ahmed treats them as such. Rather than diminish their effect, this services the narrative well, piquing the reader’s curiosity and allowing them to flood the world with their own imagined answers for how things have come to be how they are. And most importantly, it enunciates the plight and the poison of our many-named narrator. Brought in as an outsider, the world is nothing more than a hassle for our narrator at first, a series of challenges with little warmth or love. As the novel progresses, that initial sympathy reader’s feel for our narrator turns to dread and disgust as his own powerful obsessions begin to take root, and it becomes clear that we’re not dealing with just an outsider, but a madman. What is and isn’t true is thrown into question as we are trotted through the world, compelled to watch with an ever-growing sense of unease—the narrator’s plot to supplant and replace Kansas’s savior.

Though these events take place in a different space and time, an imagined Kansas of else-when and where, the moves Ahmed makes in this novel seem especially relevant and timely to today’s society, where all around us there is upheaval, change, and conflict, and among us there are many who are too busy obsessing over our own desires, to the point where we would sacrifice the good of society for the gain of ourselves. Against the backdrop of an imagined world, Kansastan shows us the making of very real monsters, and while doing so it will make you wonder, it will make you laugh, and it will make you squirm.